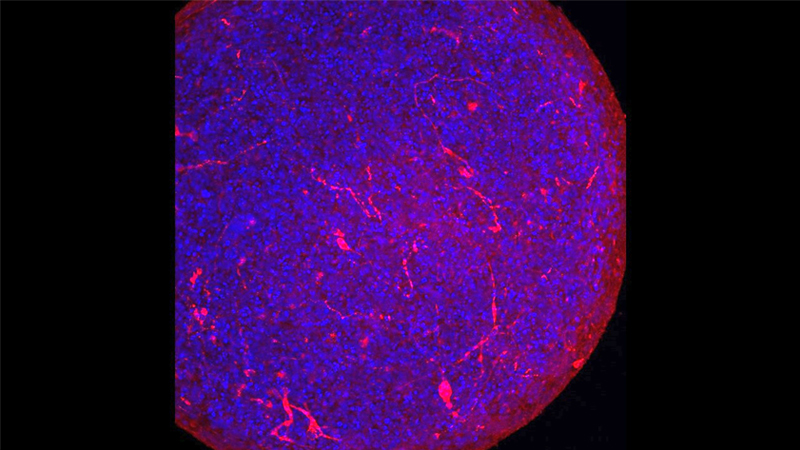

A multidisciplinary team from two Johns Hopkins University institutions, including neurotoxicologists and virologists from the Bloomberg School of Public Health and infectious disease specialists from the school of medicine, has found that organoids (tiny tissue cultures made from human cells that simulate whole organs) known as “mini-brains” can be infected by the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19.

The results, which suggest that the virus can infect human brain cells, were published online June 26, 2020, in the journal ALTEX: Alternatives to Animal Experimentation.

Early reports from Wuhan, China, the origin of the COVID-19 pandemic, have suggested that 36% of patients with the disease show neurological symptoms, but it has been unclear whether or not the virus infects human brain cells. In their study, the Johns Hopkins researchers demonstrated that certain human neurons express a receptor, ACE2, which is the same one that the SARS-CoV-2 virus uses to enter the lungs. Therefore, they surmised, ACE2 also might provide access to the brain.

When the researchers introduced SARS-CoV-2 virus particles into a human mini-brain model, the team found — for what is believed to be the first time — evidence of infection by and replication of the pathogen.

The human brain is well-shielded against many viruses, bacteria and chemical agents by the blood-brain barrier, which in turn, often prevents infections of the brain. “Whether or not the SARS-CoV-2 virus passes this barrier has yet to be shown,” notes senior author Thomas Hartung, M.D., Ph.D., chair for evidence-based toxicology at the Bloomberg School of Public Health. “However, it is known that severe inflammations, such as those observed in COVID-19 patients, make the barrier disintegrate.”

The impermeability of the blood-brain barrier, he adds, also can present a problem for drug developers targeting the brain.

The impact of SARS-CoV-2 on the developing brain is another concern raised by the study. Previous research from Paris-Saclay University has shown that the virus crosses the placenta, and embryos lack the blood-brain barrier during early development. “To be very clear,” Hartung says, “we have no evidence that the virus produces developmental disorders.”

However, the mini-brains — which model the growing human brain — contain the ACE2 receptor from their earliest stages of development. Therefore, Hartung says, the findings suggest that extra caution should be taken during pregnancy.

“This study is another important step in our understanding of how infection leads to symptoms, and where we might tackle the COVID-19 disease with drug treatment,” says William Bishai, M.D., Ph.D., professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and leader of the infectious disease team for the study.

The human stem cell-derived mini-brain models — known as BrainSpheres — were developed at the Bloomberg School of Public Health four years ago. They were the first mass-produced, highly standardized organoids of their kind, and have been used to model a number of diseases, including infections by viruses such as Zika, dengue and HIV.